Cultural Context

When the Spanish arrived on the coast of what they were to call New Spain—which included what is now modern-day Mexico—the Zapotec people had already been writing for some 2,000 years. It was therefore not surprising that they quickly adopted the alphabetic writing system. Such writing was introduced as part of an expansive undertaking that had as its objective the conversion of the indigenous population to Christianity. This project created the need for a learning process unprecedented in world history: describing and analyzing the multiple languages of Mesoamerica. The results of this project were numerous dictionaries, grammars, and religious works created by Dominican friars relying heavily on the collaboration of Zapotec speakers.

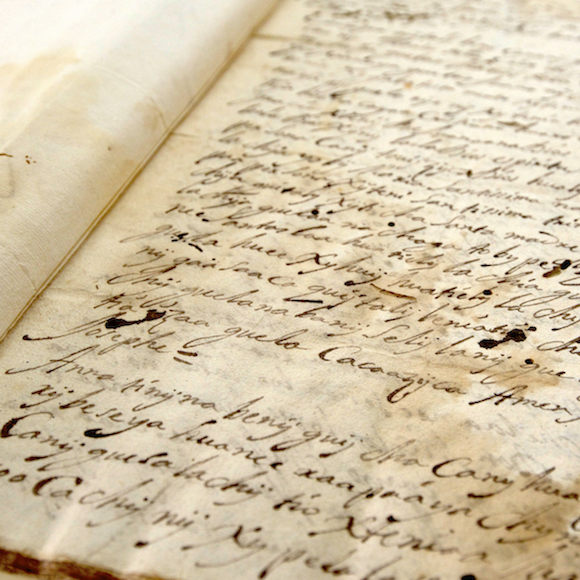

These indigenous communities began to utilize alphabetic writing to create documents in their own language for their own purposes, including wills, land titles, and songs. Researchers have identified colonial documents written in Central Zapotec, Cajonos Zapotec, Nexitzo Zapotec, and Sierra Juárez Zapotec. Today these texts are dispersed throughout local, state, national and international repositories and archives. Currently, Ticha provides access to colonial documents written in Central (Valley) Zapotec, such as the Arte a book that seeks to describe the structure of the Zapotec language, and many wills.

The indigenous language documents are invaluable sources in understanding the historical and cultural developments of Mesoamerican peoples from the beginning of the colonial period until the present day. Unlike Spanish texts, these native language documents describe the world using their own cultural categories. For example, in Zapotec wills the testator might offer his soul to God to be eaten and his body to be consumed by the earth; clear continuities of indigenous perceptions related to death. These texts, and as such the Ticha portal, are a window for contemporary indigenous communities and scholars alike to explore Zapotec history, language, and culture.

View Dizhsa Nabani, a documentary web series, to learn more about the relationship between identity, language, and daily life in the Valley Zapotec community of San Jerónimo Tlacochahuaya.

Linguistic Background

Zapotec is an extensive language family indigenous to southern Mexico, which belongs to the larger Otomanguean family Today, there are over 50 different Zapotec languages (iso code zap) most of which are endangered. They are spoken primarily in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, by a total of approximately 425,000 people (INEGI 2010) within a much larger Zapotec ethnic community. Due to immigration, there are now Zapotec speakers in many other parts of Mexico and the United States. Dialectal divergence between Zapotec-speaking communities is extensive and complicated. Many varieties of Zapotec are mutually unintelligible with one another. The Zapotec language family is on par with the Romance language family in terms of time depth and diversity of member languages.

The variety of Zapotec presented in Ticha represents the Zapotec of the colonial period of Mexico (1521-1821). During this period, hundreds of documents were written in Zapotec, including religious materials, last wills and testaments, deeds, and letters. Many of these documents were written by native speakers for use by native speakers, such as local administrative texts. Other texts were written to be used by Spanish speaking priests and were likely created in collaboration with Spanish speakers.

The texts currently available on Ticha are written in Zapotec from the Central branch, often referred to as Colonial Valley Zapotec. The Ticha Bibliography lists works written about Colonial Valley Zapotec.